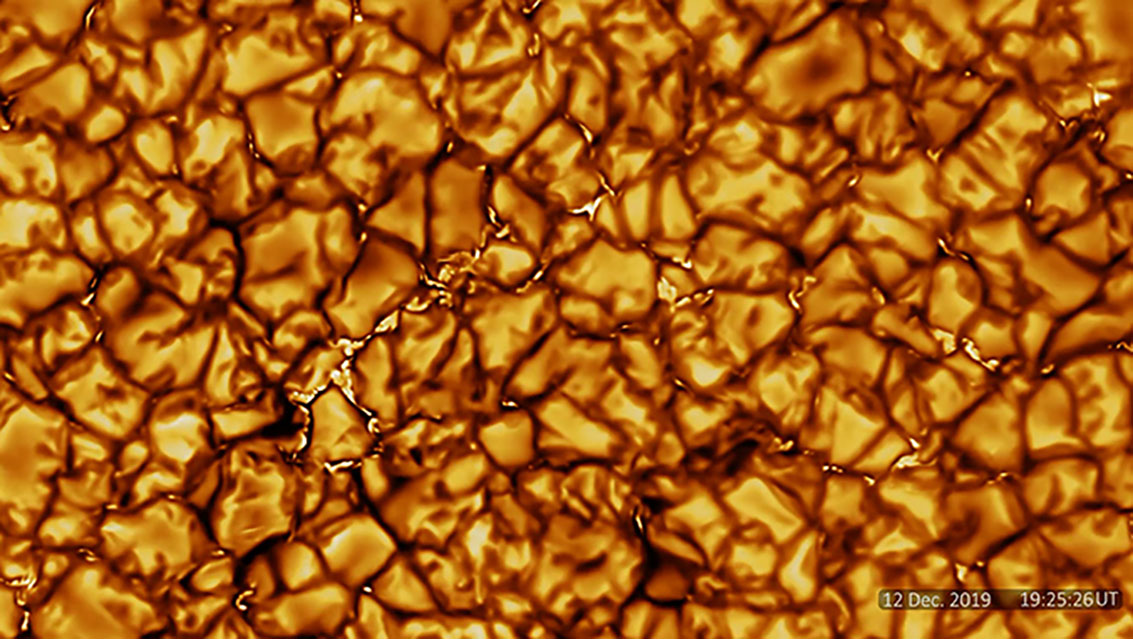

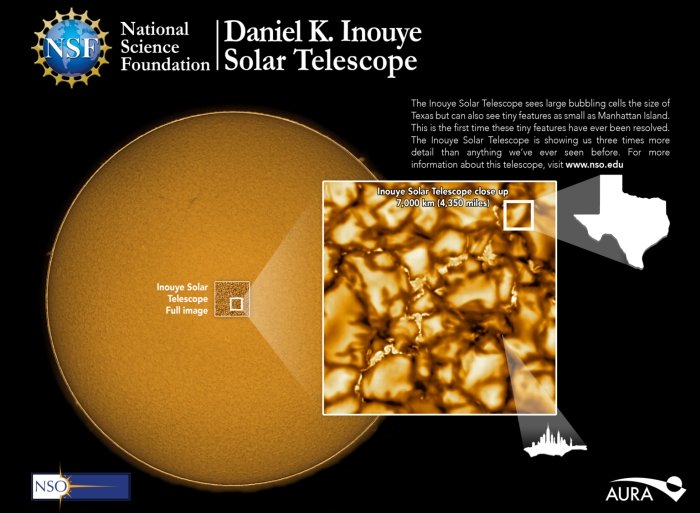

The highest resolution images ever taken of the Sun’s surface were released last week, showing in stunning detail, the planet’s life source.

The National Science Foundation (NSF) published the images on Wednesday, captured by the world’s largest solar telescope, The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST).

DKIST director Thomas Rimmele said in a press release that the extraordinary images are just the beginning. “These are the highest-resolution images and movies of the solar surface ever taken. Up to now, we’ve just seen the tip of the iceberg.”

The new DKIST telescope was built on Haleakalā in Maui to study the Sun. So far, the detailed images have superseded expectations, and according to Rimmele, will help to “unravel the Sun’s biggest mysteries.”

The sections of orange seen in the images are convection granules the size of Texas. The release of the images marks the beginnings of a 50-year study covering two of the Sun’s 22-year solar cycles. Despite DKIST’s construction starting in 2012 and that it isn’t fully operational yet, the captured images show promising results for the scientific community.

On January 23, DKIST’s Visible Spectro-polarimeter (VISP), came online. Space.com reported that VISP records precise measurements of light. “VISP splits light into its component colors to provide precise measurements of its characteristics along multiple wavelengths.”

All instruments are expected to be fully operational by mid-2020.

Astronomer Jeff Kuhn from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Institute for Astronomy is hopeful for the future studies of the Sun. “It is literally the greatest leap in humanity’s ability to study the Sun from the ground since Galileo’s time.”

Once fully operational in July, DKIST’s sensitivity to light and high resolution capabilities will allow the Sun’s magnetic field to be probed. The studies will shed light on what drives space weather and the Sun’s release of charged particles that interfere with space technology like satellites and power grids.

“On Earth, we can predict if it is going to rain pretty much anywhere in the world very accurately, and space weather just isn’t there yet,” Matt Mountain of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy said.

“Our predictions lag behind terrestrial weather by 50 years, if not more. What we need is to grasp the underlying physics behind space weather, and this starts at the sun, which is what the [NSF] Inouye Solar Telescope will study over the next decades.”