In 1999, three 500-year-old mummies were discovered on the summit of Chile’s Llullaillaco Volcano near the border with Argentina. They were in their twenties. The eldest, known as the Ice Maiden, was only 13 years old, while the other two, a boy and a girl, were thought to be four or five.

The Llullaillaco mummies are a fascinating discovery for the scientific community because they provide information on the ancient Incan sacrifice tradition. All three were most likely killed in the Capacocha ritual, in which they were sacrificed to the Sun God. Their remains were astonishingly well preserved, thanks to the cold, thin air of the highlands, which naturally turned them into frozen mummies. They appeared to have simply fallen asleep.

The Maiden, the Llullaillaco Boy, and the Lightning Girl are on display in Salta, Argentina (so named because she looks to be hit by lightning). They continue to tell stories about their interesting and tragic lives in the old Incan Empire.

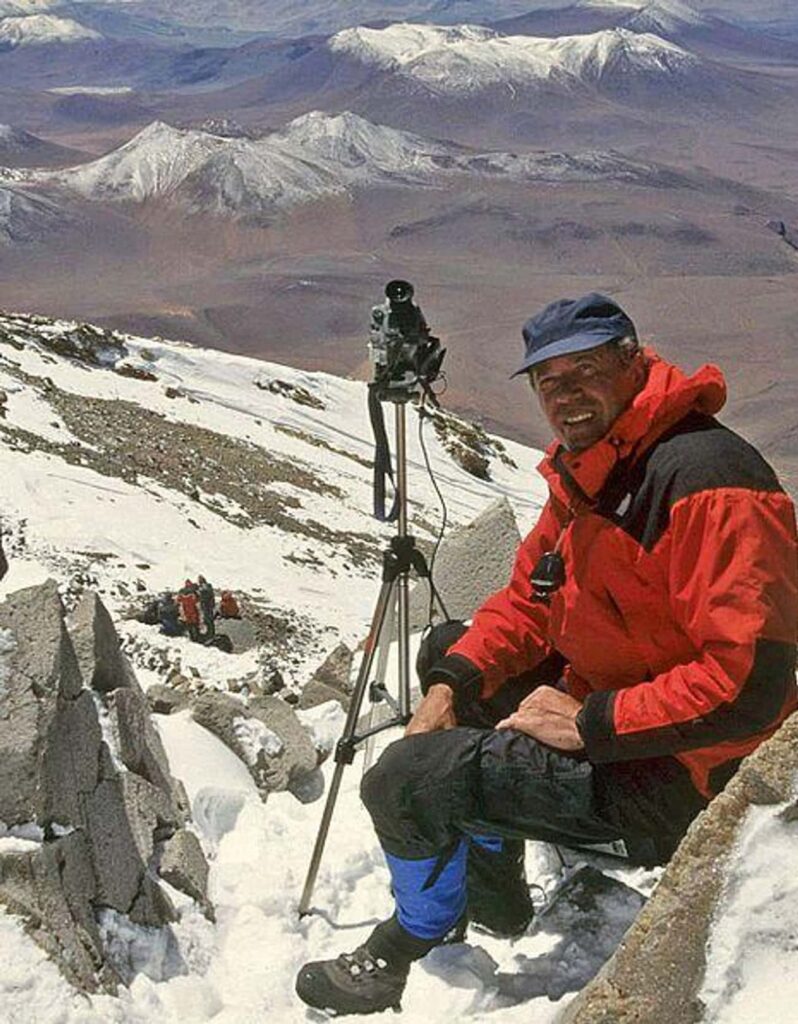

The mountaintop conditions were ideal for preserving the bodies of the children.

The three toddlers apparently froze in their sleep near the 22,000-foot summit of Mount Llullaillaco. In contrast to other mummies from around the world, no natural or man-made compounds were used to preserve the remains. The tissues remained intact despite the freezing temperatures and extremely dry, thin air. Their bodies were practically frozen.

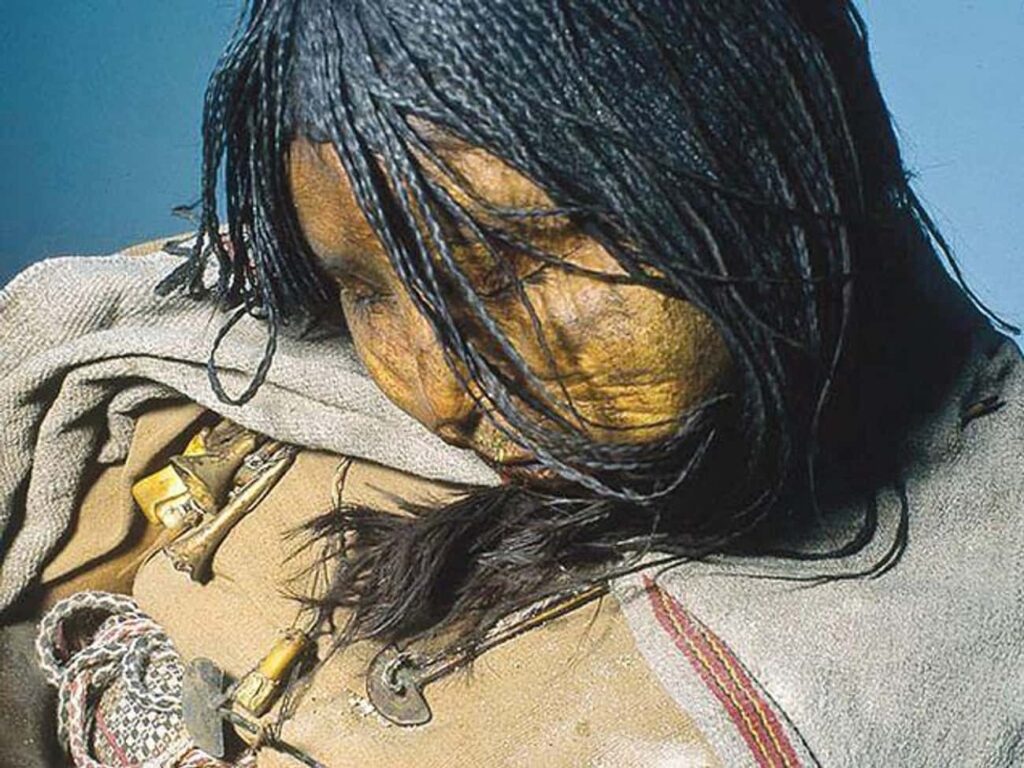

The children are among the best-preserved mummies in the world. The remains’ hair, skin, facial features, blood, and internal organs are all completely intact, providing scholars with a wealth of information about the lives of the Incan sacrifices.

All Three Children Showed Signs Of Drug And Alcohol Use

According to experts, the children, particularly the elder daughter, spent their final year in Cusco, Peru, the capital of the Incan Empire. She spent the previous year preparing for her journey to the mountain by “weaving fabrics and brewing chicha.”

Chicha, a corn-based drink, and the coca leaf, from which cocaine is derived, were both popular in Inca civilization. Both, however, were prohibited drugs that were not accessible to the general public. Hair tests revealed that the children’s intake of chicha and coca grew dramatically in the year before their deaths.

This was especially true for the 13-year-old girl, who had surges in usage around six months before her death, and then again in the month before the tragedy.

Experts believe the liquor and drugs were either part of the festivities they attended or were used to sedate the youngsters during the sacrifice. A coca package was also discovered in the girl’s mouth, which may have served to calm her in her chilly grave.

Using Hair, Researchers Gained A Wealth Of Information About The Mummies’ Former Lives

The discovered 13-year-old Ice Maiden’s long, beautifully braided hair provided experts with significant evidence. Hair is a record of what is going on in a person’s life. Scientists studying the Llullaillaco mummies were able to piece together a timeline of the children’s final year of life because they grew at a consistent rate of one centimeter per month.

An examination of the children’s hair revealed what they ate, with their diets gradually shifting to include more expensive items like beef and maize (corn). It also revealed that their consumption of chicha (corn-based beer) and coca had increased, peaking at different times of the year. This was said to be related to their attendance at festivals prior to their sacrifice, as well as their preparation for death.

The Three Children Most Likely Had Very Different Roles

According to research, the three Llullaillaco mummies were unrelated, though they may have had similar beginnings in life. According to some accounts, all three children were born into low-income families and rose to “elite rank” through their service to the empire.

According to legend, the two younger children were already on a higher social level than the elder female, and were possibly royalty. Their elongated heads, most likely the result of deliberate head-wrapping, indicate their upper-class status.

Whatever start in life the two younger children had, their duty in death appeared to be to be the elder girl’s attendants. Despite the fact that all three died during the Capacocha ritual, only the third survived.

Whatever start in life the two younger children had, their duty in death appeared to be to be the elder girl’s attendants. Even though all three died in the Capacocha ritual, only the elder girl received obvious special attention prior to death. She was also the only child with intricate braids, while the boy had nits in his hair.

The older girl’s death was most likely peaceful, but the young boy displayed signs of struggle.

The burial site of the Llullaillaco mummies was peaceful. The religious artifacts surrounding the mummies were untouched, and the children appeared to be sleeping. The younger girl was dubbed the Lightning Girl because lightning partially scorched her body long after her death, despite the fact that she most likely slept peacefully in the icy tomb. The Llullaillaco Boy, on the other hand, might have struggled, especially since there was some blood on his clothing.

Many of the Capacocha sacrifice sites are violent, and not all are peaceful. “Either they did it perfectly, in terms of honing the procedures of making this type of sacrifice, or these youngsters went much further than they should have.”

The children appeared to be sleeping, which was unsettling the researchers.

When working with mummies, scientists frequently work with bones, dried flesh, and features that no longer resemble human faces. However, with the Llullaillaco mummies, researchers worked with what appeared to be living remains. The Museum of High Altitude Archaeology’s director, Dr. Gabriel Miremont, told the New York Times that working with the three children felt “almost more like a kidnapping than archeological labor.”

Archeological expert Andrew Wilson commented on the astonishingly well-preserved bodies in a 2013 interview:

“That, I believe, is what makes this so frightening. This is not a mummy or a collection of bones. This is a person; this is a child. Furthermore, the information gleaned from our research points.”

Being chosen for sacrifice may have been considered an honor among the Inca.

According to research on the three mummies, the children lived ordinary lives within the Incan Empire until the elders chose them to gain higher status through ritual sacrifice. Although modern thinking regards child loss as a tragedy, the ancient Incas apparently felt proud if their child was one of the few chosen to serve as a sacrifice.

Some analysts believe the sacrifices served a religious purpose as well as a form of psychological control. It was extremely disrespectful if parents displayed any signs of sadness after choosing their children.

The Andes Mountains were sacred in Incan religion.

Although the alpine climate was ideal for preserving human corpses, the Incas had another reason for using the Andes peaks as sacrifice sites. Because their religion revolved around the Sun God, Inti, and the summits were the closest they could get to the sky, the mountains were very important to them.

The Incas endured extreme and dangerous weather conditions at high altitudes in order to deposit human sacrifices, which were later thought to be angelic creatures watching over the empire, ensuring safety and prosperity throughout the empire.

The child sacrifices could have been used to gain power by the ruling class.

The heart of the Incan Empire was in Cusco, Peru, but by the time of the children’s sacrifice, it had spread up and down South America’s western coast. The children would have attended various festivities throughout the empire prior to their sacrifice at the Llullaillaco Volcano. The volcano is located on the border of modern-day Chile and Argentina, in one of the most southern regions of the Incan Empire.

Some analysts believe that as the empire’s borders expanded, the authorities wanted to send a message. The child sacrifices created a “climate of terror” as a demonstration of the Incan Empire’s strength.

These three children were not the only ones who became stranded in the mountains.

The Ice Maiden, Lightning Girl, and Llullaillaco Boy are some of the world’s best-preserved archeological artifacts, but they were not alone on the Andes peaks.

There were over 100 additional cemeteries or sacrifice sites within the Incan Empire, with mummies in various states of preservation. One mummy known as the “Reina del Cerro” (Queen of the Hill) was discovered in 1995, while another known as the “Juanita” (Queen of the Hill) circulated among private collectors for decades after its discovery in the 1920s.

These mummies, along with the three Llullaillaco children, are housed in the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology in Salta, Argentina.

Because earthquakes are common in the area, there are several backup plans in place to keep the mummies safe.

Because South America is prone to major earthquakes, storing extremely sensitive mummies is difficult. If the facility loses power, the mummies, which are kept in climate-controlled conditions, may decay quickly.

The Museum of High Altitude Archaeology took several precautions to prevent power outages from damaging the mummies’ cases. The museum has three backup generators. In the event of an emergency, the governor’s jet can transport the mummies anywhere there is a steady supply of electricity.

The Mummy Exhibit Takes Both Practicality And Sensitivity Into Account

The three mummies are now housed at the Museo de Arqueologa de Alta Montaa in Salta, Argentina (Museum of High Altitude Archaeology). Their exhibits required extensive planning, particularly because the mummies are so delicate and valuable to both science and local culture. The museum chose a display that reflects both the physical demands of the mummies and the reverence they believe these hallowed remains deserve.

The corpse displays (usually only the 13-year-old girl’s, with the other two remaining in storage) are tube-like containers with temperature controls. Because the sight of dead bodies disturbs many people, the curators designed the display to be completely dark until someone wants to see the body and turns on the light.

Since its inception, the exhibition has been respectful of the Incan culture. The museum’s director, Dr. Gabriel Miremont, stated in an interview that the exhibit was launched quietly for a reason: the bodies were once real people, and while it was an exciting occasion for scientists, it was not “a circumstance for a celebration.”