During its years of operation, the Soviet Union was full of secrets. While outsiders often wondered what was going on behind the Iron Curtain, most citizens were kept in the dark as well.

Between the secret police force prowling the cities for dissidents and gulags in the Siberian country side, there was plenty the average Soviet didn’t — or simply wasn’t supposed — to know. The biggest secrets were kept far from prying eyes.

And where can you keep massive government projects hidden? Well, if you’re a Soviet official, you keep your biggest secrets under wraps in what are called “closed cities.”

Closed cities were special areas controlled by the Soviet government. While people lived and worked there, only authorized citizens could enter the city via checkpoint. Most closed cities were kept off official maps, hiding them from the world.

One of those cities was City 40, now known as Ozyorsk. It sits near a lake just south of Yekaterinburg, but the city was far from a rural paradise. In fact, authorities had to convince residents to live there.

Because as you might imagine, living in a secret city wasn’t exactly desirable. So, the Soviet Union had to get creative in convincing residents to deal with a life of security checkpoints and isolation.

Their offer? Residents of City 40 were provided with apartments, healthcare, and other privileges that the rest of the country could only imagine. Grocery stores were always fully stocked. But those perks came at a price.

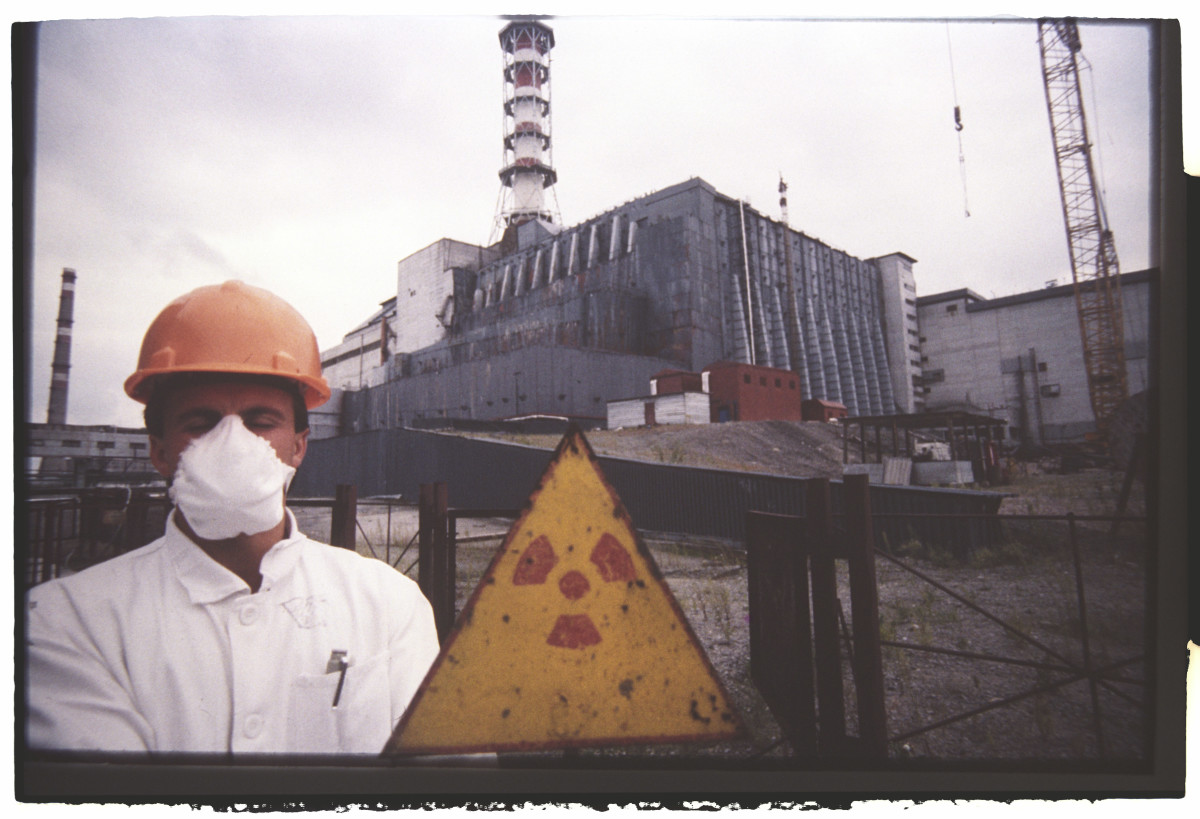

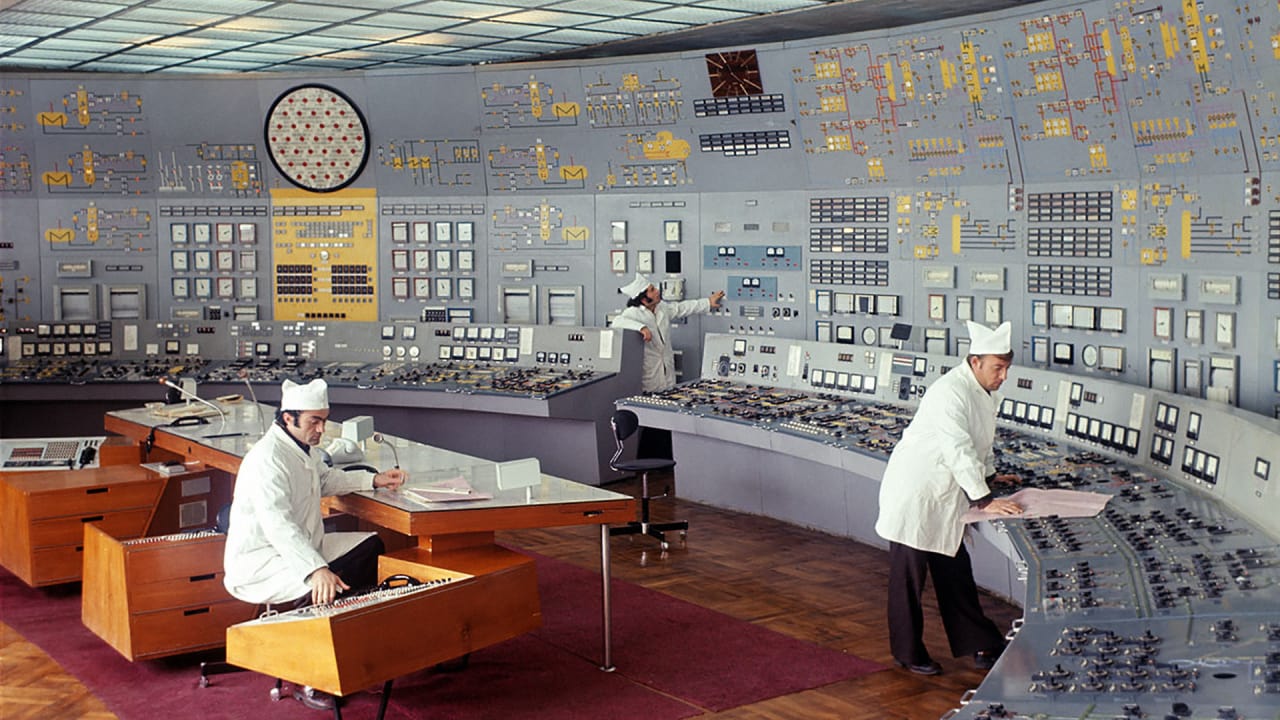

See, those living in the closed city were subjected to some of the most dangerous work possible, as they would be the driving force in one of the world’s first-ever plutonium processing plants.

At the time, the Cold War was ramping up and the Soviet Union couldn’t fall behind the United States. Losing out in the arms race could be a death sentence for the nation. Politicians knew they had to take action.

So City 40’s citizens powered the war effort, processing plutonium for nuclear weapons. And while that job was far from a picnic, there was still something worse going on behind the scenes.

After the plutonium was processed, the plant was left with nuclear waste, which, as we now know, is a massive safety hazard. Worse, authorities weren’t disposing of that waste properly. They were simply dumping it into the environment.

Exposure to radiation can have all sorts of side effects, ranging from immediate radiation sickness to longer term cancers. How could the Soviet Union get away with poisoning their own citizens?

Well, given that the plant was in a closed city, the authorities could more or less do as they pleased. The outside world didn’t know the city existed deep in the forest, let alone that it was being poisoned.

Over the plant’s lifespan, it’s estimated that the amount of contamination released was two to three times larger than Chernobyl. But the pollution hit one area harder than the others.

City 40 was built alongside the Techa River, which felt the brunt of the dumping. While the river and its surroundings are still radioactive to this day, it also carried a large amount of the pollution elsewhere.

The river runs into Lake Karachy, which once looked like a perfect place to stop for a swim in the Russian countryside. Now, you wouldn’t want to even think about dipping a toe in that radioactive water!

Today, that ordinary-seeming lake is one of the most contaminated spots in the entire world. Known as the Lake of Death, the body of water was reportedly at least twice as radioactive as the heart of Chernobyl.

In fact, the pollution was so deadly that the Russian government finally took steps to contain it. The lake was filled with concrete blocks and eventually covered with layers of rocks and dirt, turning it into a permanent waste storage facility.

Despite all the hazards, some people still call Ozyorsk home. The passing of time and all sort of health risks simply can’t overpower the pull that keeps them anchored to the former City 40.

Ozyorsk is still technically a closed city, making residents hesitant to leave. Not only would they be leaving everything the government provides for them behind, but they could never return to the area.

It all comes down to a simple reality: even in a contaminated city that was kept off the map for decades, there’s no place like home.