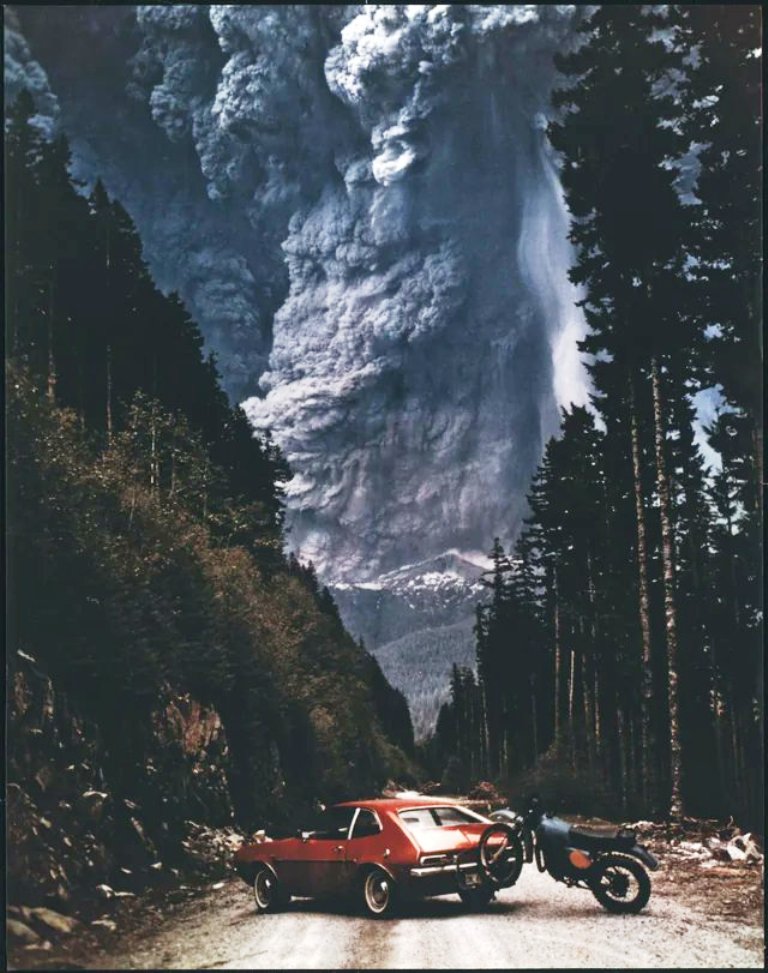

A massive cloud of ash rises in the distance, swirling with malice and terror, with lightning arcing inside it. As if to emphasis the danger, the canyon of trees that frames the grey skies has darkened towards the heights, obscured by unseen approaching ash clouds. One shaft of dawn light still reaches the lower branches of the trees, spilling over a cut of foliage and the least likely sight in the photo: a red Ford Pinto slanted across a forest road with a blue dirt bike strapped to its bumper.

Even if you haven’t visited the Johnston Ridge Observatory near Mt. St. Helens, where one of the most perplexing photos of the volcano’s May 1980 eruption is prominently displayed, you’ve almost certainly seen the photo circulating on the Internet, stripped of all context except the date and location. You’ve probably also pondered who shot the photo, what they were doing up there in the first place, and if they made it out alive. We felt the same way, so we went out to find whatever answers we could. Some came easily, while others did not.

To begin with, almost everyone in the Pacific Northwest was aware that Mt. St. Helens was poised to explode. It erupted in the mid-nineteenth century, and by early 1980, seismologists were watching a big bulge on the volcano’s north slope. Officials had began evacuating nearby inhabitants as a precaution, but they couldn’t deter campers from circling the volcano’s base, especially on a bright mid-May weekend.

Richard “Dick” Lasher spent Saturday night preparing his kit, planning to leave first thing in the morning to see the mountain before it exploded. His goal was to attach his Yamaha IT enduro cycle to the back of his Pinto, drive up to Spirit Lake, and then explore the region on the bike through dirt forest roads. He’d depart before morning and get to the lake before sunrise.

Lasher was a “very old school silent type,” according to Gary Cooper, a former coworker at the Boeing plant in Frederickson, but he ended up relating the tale of the Mt. St. Helens photos to a lot of friends and coworkers over the years. He’s now retired and has turned off his phone and Facebook account. Nobody we’ve spoken with who knew him appears to know how to contact him anymore, and another of the three Richard Lashers in Washington with whom we contacted was aware of the image but unaware of the photographer. Having said that, enough of the tale has been told and repeated from many sources for us to feel comfortable publishing it here.

Lasher slept in an hour or two past his scheduled departure time, exhausted from packing. He claimed many years later while relaying the story that sleeping in that morning saved his life. Based on the perspective of the shot and the surrounding topography, it appears Lasher drove down into Spirit Lake from the north, most likely descending down from U.S. 12 and the town of Randle onto Gifford Pinchot National Forest forest roads. He may have gotten as far south as Forest Road 26 by 8:32 a.m.

When the volcano erupted.

Lasher would probably definitely have perished if he had made it to Spirit Lake. Spirit Lake “received the full shock of the volcano’s lateral explosion,” according to John P. Walsh’s description of the eruption. The sheer intensity of the detonation drove the lake out of its bed and 85 storeys into the air, splashing onto surrounding mountain slopes.”

If Lasher had made it over the next crest, he would probably definitely have perished. According to Cooper’s account, “luckily for him, and he did not understand until later just how lucky, he was on the opposite side of that slope in front, because the entire forest was flattened from the crest down, and he was on the lee side and sheltered from most of the blast.”

He did, however, recognise that he needed to get out of there quickly. Despite the fact that the volcano ejected a pyroclastic flow almost directly north of Lasher, one graphic suggests that temperatures around Lasher’s location reached 680 degrees Fahrenheit. The majority of the 57 individuals who perished that day, according to the same map, were located to the north or northwest of the volcano, although at least four of them were in Lasher’s neighbourhood.

According to Cooper and fellow former coworker Steven Firth, some of the images Lasher ended up capturing of the aftermath focused on individuals who didn’t make it out alive and the vehicle carnage they left behind. Cooper and Firth both remembered Lasher showing them photographs of burned-out trucks with molten plastic below.

So, indeed, the photographer behind that mysterious shot lived to see it widely circulated. We don’t know what happened to the Pinto and the Yamaha, but if you have a red Pinto hatchback with a lot of volcanic ash in the seams, get in touch with us.