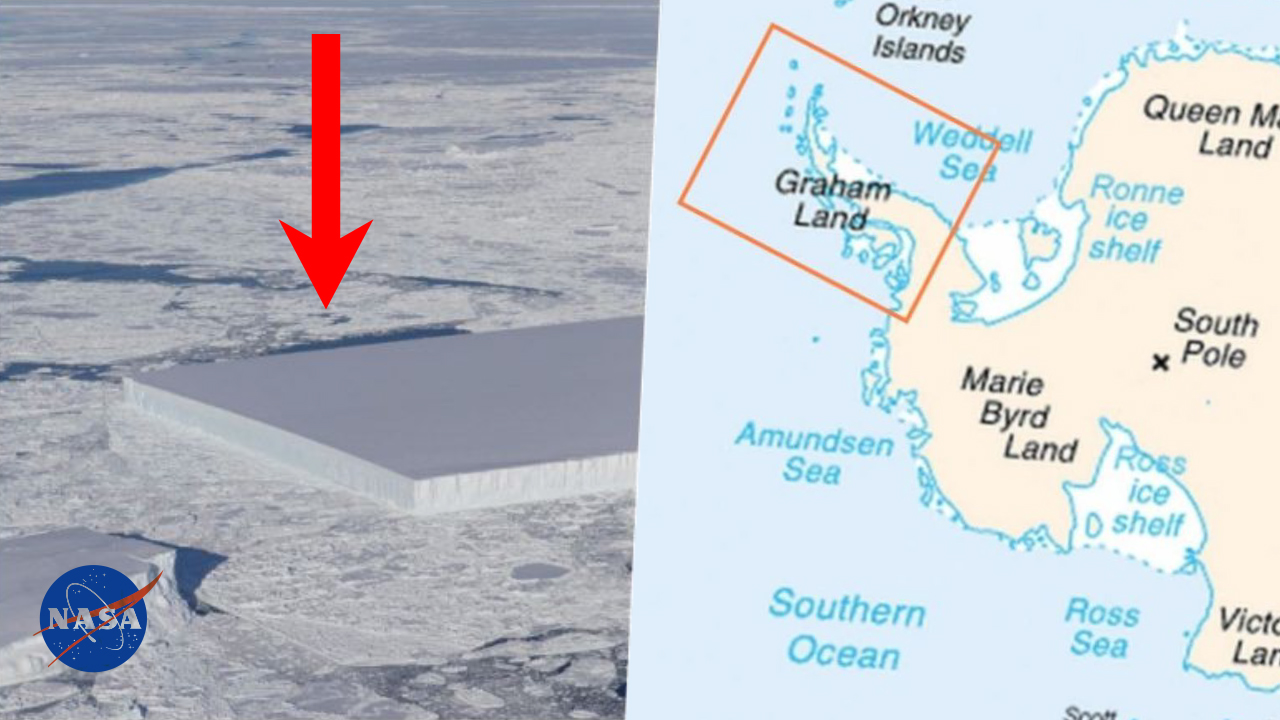

NASA just made headlines across both the mainstream media and the underground, with their photo of an incredible, almost perfectly rectangular iceberg in Antarctica.

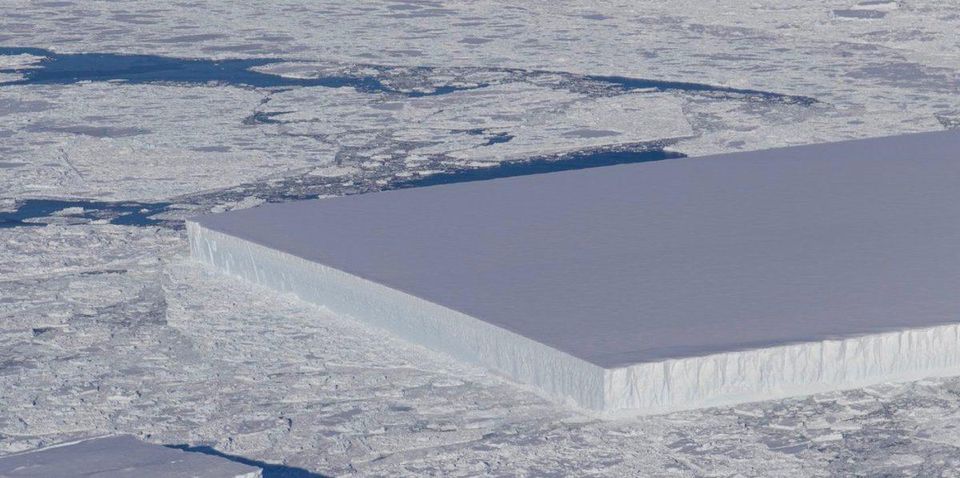

Located just off of the Larsen C ice shelf, this absolutely monolithic slab of ice appears to have been cut deliberately. Whatever caused it to form, it appears extremely unnatural.

The photo was taken by NASA as a part of their Operation IceBridge, which is said to be a mission set out to image the polar regions of Earth for the purpose of understanding how ice has been changing in the past several years. In specific, the mission is to determine how the ice has been changing in terms of thickness, accumulation, and location.

NASA claims the iceberg is an entirely natural phenomena, and it’s called a “tabular iceberg.”

The official narrative is, tabular icebergs feature steep, almost vertical sides with a flat plateau on top. They typically crack and break off of ice shelves, and those are less perfectly tabular bodies of thick ice.

According to a NASA page involving an aspect of Operation Icebridge:

“NASA’s decade-long airborne survey of polar ice, Operation IceBridge, is once again probing Antarctica. But this year is different: it is the first time that the IceBridge team and instruments survey the frozen continent while NASA’s newest satellite mission, the Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite-2 (ICESat-2), studies it from space.

After successfully flying over the Bailey Ice Stream and Slessor Glacier in East Antarctica on Oct. 10, IceBridge will spend the next five weeks measuring changes in Antarctic sea and land ice while precisely flying under orbits of ICESat-2 to compare measurements.

IceBridge began flying in 2009 to maintain continuity of laser-altimetry measurements between NASA’s ICESat missions. The original ICESat mission ended in 2009, and its successor, ICESat-2, was launched this past Sept. 15. Since then, ICESat-2 has successfully collected its first height measurements across the Antarctic Ice Sheet on Oct. 3.”

“We’re going to be chasing sea ice,” said IceBridge’s deputy project scientist and a sea ice researcher at Goddard, Linette Boisvert, speaking on some of the ways they are studying ice. “To do so, we will take the plane down to a lower altitude and remain there for a few seconds to measure wind speed and direction. We’ll plug these data into a code that accounts for drift and other forces, calculating where the sea ice that ICESat-2 flew over is currently located. Then, we’ll adjust our route to fly over it. On the way back to base, we’ll drop lower again to measure wind speed, readjust our trajectory and chase sea ice again.”

The iceberg in this case must be very young, as soon wind, waves, and all those usual factors will cause the sharp edges of the iceberg to become rounded.

Most people know only a tiny 10 percent of an iceberg usually sits above the surface of the ocean when it is floating. It’s unclear however, in this photo whether it goes deep underneath the water.