They are spectacularly super-rich. But they don’t splurge on yachts. They invest in the environment. They buy up land and turn it into national parks. They have funded national parks over vast tracts of the South African wilderness. Some have intervened to halt development in remote Patagonia. Others have established a wildlife reserve in 250,000 barren acres of South Australia.

Many have paid out small fortunes to protect mountain ranges in northern Spain or to save Highland peaks and glens in northern Scotland. In rural Sussex, a “rewilding” project has converted agricultural land into a minor miracle of conservation and landscape renewal.

Over the next decade, members of Foundation Conservation Carpathia (FCC), a conservation initiative of epic ambition, are determined to create a 200,000-hectare national park in Romania – which will be nothing less than a “European Yellowstone” – in one of the most beautiful virgin forest landscapes in the world.

Meet the Knepp group, billionaire men and women dedicated to saving the world!

83-year-old Hansjörg Wyss, the Swiss billionaire who in November 2018 announced he was giving away $1 billion to accelerate conservation efforts on land and at sea with the goal of protecting 30% of the Earth’s surface by 2030, has donated $450 million to wilderness projects in South America, Europe, Canada and Mexico. Wyss, whose personal fortune is estimated at $5.7 billion, is also the largest investor in the African Parks Trust.

Danish businessman Anders Holch Povlsen, CEO and owner of the international clothes retailer chain Bestseller (which includes Vero Moda and Jack & Jones), invests the profits in the Scottish Highlands. Povlsen, whose personal fortune is worth an estimated $6 billion, is the largest landowner in Scotland. With a total holding of more than 220,000 acres, Povlsen wants to reverse years of land mismanagement and restore the Highlands after several centuries of damage from overgrazing by sheep and deer.

Markus Jebsen, 56, known for his family’s 120-year trading history in Hong Kong, is a passionate campaigner against the ivory trade. He has invested in environmental projects across four continents; one project in South Australia is devoted to removing feral cats and foxes from a 250,000-acre natural reserve.

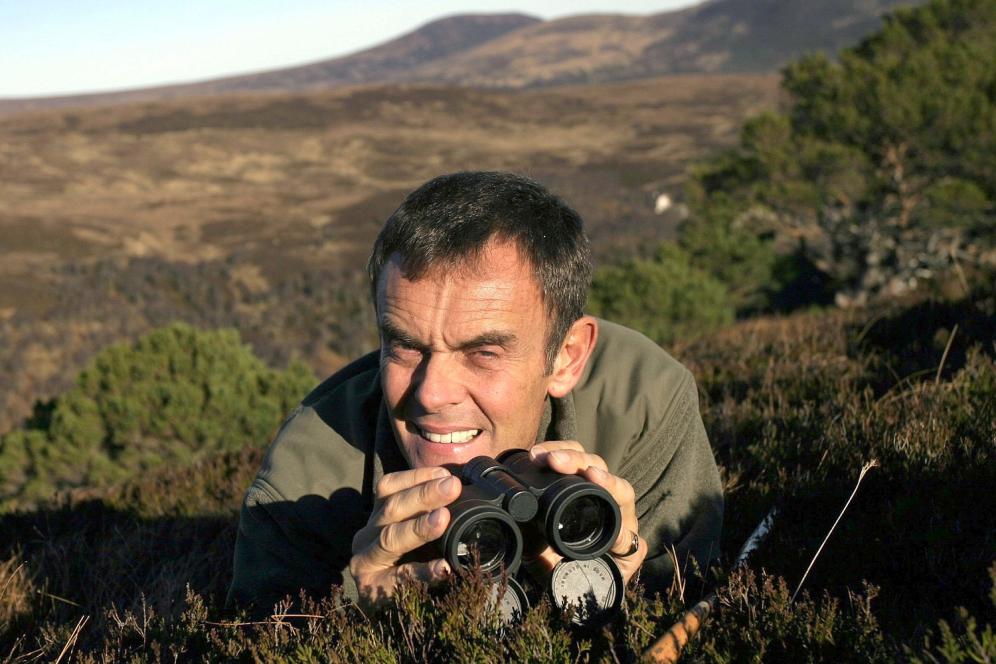

Paul Lister, who inherited an estimated £50 million when his father died, acquired the 23,000-acre Alladale estate, 50 miles north of Inverness (Scotland), for £3.2 million in 2003 and immediately set about creating a wilderness reserve. Often considered eccentric by ramblers and conservationists, Lister has planted 850,000 trees in one of Scotland’s most unique conservation projects, that is a natural paradise for eagles, otters, peregrine falcon and red deer.

Through his foundation, the European Nature Trust, he is funding wildlife restoration and protection projects in Asturias, Spain, Abruzzo National Park in central Italy, and in Belize, along its border with Guatemala. For Lister, greening the planet is a matter of life or death. He tells The Times:

“People should be more conscious of the world around them, global warming, the extinction crisis and so forth. You can spend your philanthropic money on healthcare, education, disaster relief or art, but unless you worry about the environment, there is nothing else to concern yourself with. The 4 per cent that goes into the environment? That needle has to shift.”

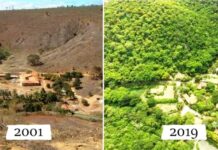

Sir Charles Burrell, 57, who commissioned the modern Knepp Castle from the Regency architect John Nash, and his wife, author Isabella Tree, phased out farming on the 3,500-acre estate in 2001. Today, in Knepp Castle, the headquarters of the 1st Canadian Division during WWII, hundreds of red and roe deer roam free and there are Tamworth pigs and Exmoor ponies. In summer, the estate is a stronghold for turtle doves. In winter, it is teeming with life, animals rooting through the meadows, jays screeching in the trees while stonechats flit among the hawthorn.

Burrell is also the host and chairman of the Foundation Conservation Carpathia. Seeds of the Carpathian reserve were sown when Hedi Wyss, 78, joined a wildlife tour in Romania in 2003 where she met Christoph and Barbara Promberger. Stretching across 1,500km, the Carpathians are one of the natural wonders of the world, comprising 6 million hectares of virgin forest covered by rocky mountains. In this wilderness, the Prombergers set up a project to document the lives of the large carnivores. Hedi agreed to fund tagging projects for wolves and lynxes over a number of years.

In 2007, when the Piatra Craiului National Park was about to lose control of almost half of its 15,000-hectare estate to timber companies, the Prombergers, Hedi, Hansjörg, Lister, Jebsen, and Povlsen, came together to invest in sustainable forestry and the ambition of the environmental project. The Times writes:

“With the Prombergers supervising as joint executive directors, almost 22,000 hectares of forest have been purchased outright and are under full protection. A further 700 hectares have been restored, with 1.8 million trees planted. A hunting-free area of 36,000 hectares has been created, and will soon be expanded. The next steps require the government of President Klaus Iohannis to make a matching commitment, and for local communities to come on board.”

Doug Tompkins, founder of the North Face and Esprit clothing companies, used his fortune to preserve 2.2 million acres in South America with his wife, Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, before he was killed in a kayaking accident in 2015. Starting early 90s, the couple converted 480,000 acres into five national parks. At the time of his death, Tompkins was working with the Chilean government to establish another seven on the remainder of the land. Hansjörg recalls:

“He was a great man and a brilliant businessman. I remember when he started coming to the Romanian board meetings as a guest, and his theme was always, ‘This has to be a national park.’ I had a lot of fights with him. I said, ‘Look, Doug, sometimes it’s not possible to do everything straightaway. We need international protections for the area first, then eventually government will come in.’ But he was great because he challenged people.”

The actions of the members of the billionaires’ club at Knepp have shown that wherever a wilderness is under threat, philanthropy can make a difference. The Times notes:

“They are all members of an extraordinarily exclusive group. It’s not just that they are uncommonly wealthy – on a spectrum between castle-owning baronet and spectacularly rich tycoon. They are part of an intimate network of the super-rich who invest in the environment. Welcome to Club Billionaire, dedicated to saving the world.”