Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’d know that there is an insect ‘apocalypse’ happening in the United States. Apparently, agricultural landscape of the most powerful country in the world is now 48 times more toxic to honeybees, butterflies, as well as birds, thanks to the widespread use of neonicotinoid pesticides.

Neonicotinoid pesticides attack the central nervous system of insects, causing overstimulation of their nerve cells, paralysis and death. Incredibly toxic to insects, they remain toxic for more than 1,000 days in the environment. In April, a major study warned that 40% of all insect species face extinction due to pesticides.

The massive decline of insect populations is an environmental crisis that is often overlooked. However, researchers are developing alternatives that have the potential to protect crops with least adverse consequences on the environment.

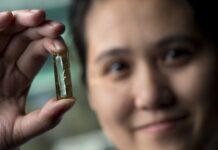

Famous mycologist Paul Stamets recently developed two fungi-based pesticides that can kill insects that destroy crops without hurting humans or environment. One of the products is specifically targeted toward fire ants, carpenter ants, and termites, while the other can affect roughly 200,000 insect species. Truth Theory writes:

“One of the fungi-based biopesticides, called MycoPesticide, will begin to sprout inside of the insect once it is eaten and will then feed on the creature until it dies, often with mushroom sprouts popping out of its head. It is also not harmful to bees, which has been a growing concern in relation to pesticides.”

While biopesticides – grown from fungi, insects, plants, bacteria, and certain minerals – can replace chemical pesticides as a less poisonous way to keep crops insect-free, the problem is one of costs.

Paul Underhill, co-owner of the organic Terra Firma Farm in Winters, California, says: “Some, like those with fungi, can require special storage, such as refrigeration. [And] the cost to the farmer can easily be 20 times what a conventional pesticide might be.”

There is another issue: Biopesticides can be more sensitive to environmental conditions, including relative humidity and temperature and exposure to UV radiation.

However, according to NPR, scientists are working with transgenic strains to improve fungi’s ability to kill insects, tolerate adverse conditions and, extending beyond crops, fight against the transmission of diseases such as West Nile virus, Lyme disease and malaria.

Ioly Kotta-Loizou, research associate in molecular biology at Imperial College London, and Robert Coutts, research fellow, department of life and medical sciences, University of Hertfordshire, note:

“It may not be possible to entirely replace chemical insecticides with fungal-based ones because the growth of fungi depends so much on environmental conditions. In the field, fungal-based insecticides can be combined with chemical insecticides (integrative pest management). Similar approaches are known to reduce chemical use by an average of 75% and increase yields by an average of 40%. This makes fungal-based insecticides a promising way to reduce chemical use and further research will help expand their use in the future.”