The world’s full of ocean deserts. The concept sounds odd, but biologists are discovering more every day as they study areas of ocean perceived as not “rich” with marine or sea life.

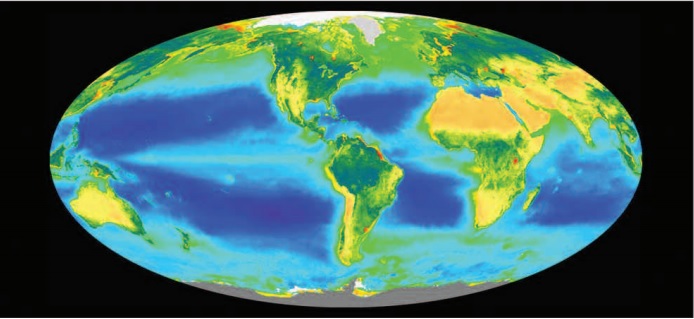

Just like the deserts above land, these “biological deserts” are considered the lowest level in the ocean food web. The ocean deserts studied today consist of mainly phytoplankton. These tiny ocean plants, which are abundant and productive, convert carbon dioxide into organic carbon. The green chlorophyll produced during the conversion process is visible from space.

The chlorophyll is being monitored by satellite, and scientists are using the data to track ocean productivity. According to ocean biologist and satellite data devotee Jeffrey Polovina, the results are concerning. Polovina and others are predicting that the warmer sections of oceans will become less productive over time, partially due to climate change.

“We saw that the low-productivity area of the west Pacific was expanding, and we wondered if it was unique or if it was happening globally,” Polovina explained. “The climate models are on century timescales and suggest that the rate of expansion of these expected low-productivity areas will be slow.”

Despite the slow moving nature of expansion, the new area of global ocean desert spans across 2.5 million square miles and represents around a 15 percent increase between 1998 and 2006.

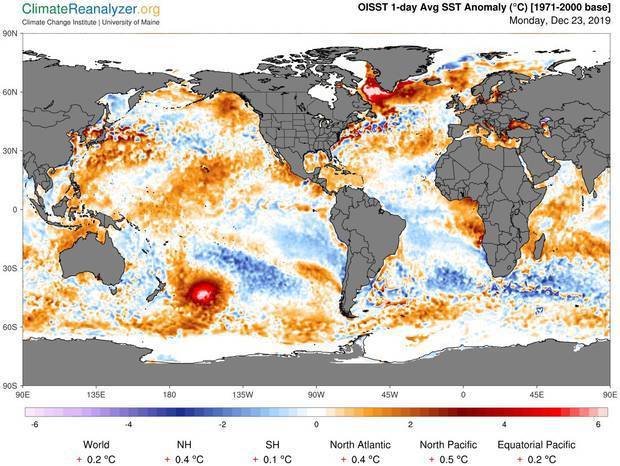

“We were very surprised. We looked at the North Atlantic, the South Atlantic, the Indian Ocean—we saw the same trends all over the globe. Over nearly the past decade, regions with low surface chlorophyll were expanding into nearby ocean basins. The total area lost was quite enormous,” Polovina said of the findings, saying the expansion matches with the increase in sea surface temperature.

Polovina continues to try and answer the question of why ocean deserts are expanding, unwilling to lay blame on global warming entirely. There are plans to expand the research to thirty or more years to provide a better picture that includes the planet’s natural cycles El Niño and La Niña.

“During the period of our study there have been several La Niña events, so the large-scale climate has been unique,” Polovina said. “It’s possible that the trend will reverse in the coming decade. Or, it could be that the trend holds, and the losses really are worse than what models are indicating they should be.”

With areas of ocean heating up at unprecedented levels of 6 degrees or more and growing larger, particularly off the eastern coast of New Zealand, the expanding ocean deserts are concerning.

According to Polovina, the long-term effects, despite the cause, could be devastating. Changes to the ocean food webs could have lasting impacts on fisheries.

According to Polovina, the long-term effects, despite the cause, could be devastating. Changes to the ocean food webs could have lasting impacts on fisheries.

“This is a unique biological signal that we’re seeing. What this means is that the ability of the oceans to support life has decreased,” he said.