An “small” nature conservation experiment that has been forgotten almost two decades after it came to fruition, has produced an amazing environmental benefit.

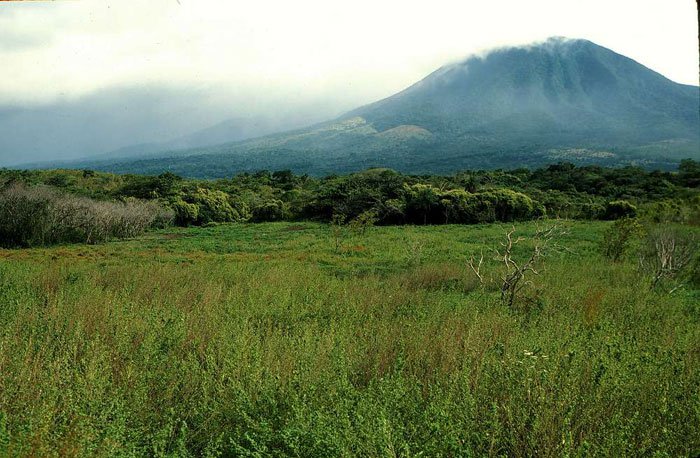

The plan, in which a fruit juice company in Costa Rica deposited 1,000 truckloads of orange peel waste on a barren pasture back in the mid-1990s, finally turned this desolate location into a thriving, lush forest.

This is a huge turnaround, especially since the project had to be stopped in the second year – but despite the premature termination led to the already deposited on the 3-acre grounds orange peel to a gradual increase of above-ground biomass by 176 percent.

“This is one of the few examples I’ve ever heard of using cost-effective carbon sequestration,” says Timothy Treuer, an ecologist at Princeton University.

“It’s not just a win for both sides, for the company and the local park – it’s a win for everyone.”

The plan was originally born in 1997, when the Princeton researchers, Daniel Janzen and Winnie Hallwax, turned to orange juice maker Del Oro in Costa Rica.

If Del Oro agreed to donate part of its land bordering the Guanacaste Reserve to the National Park, the company could deposit its orange peel for disposal on wasteland in the park for free.

The juice company agreed to the deal, promptly dumping around 12,000 tons of orange peel, carried by a 1,000-truck convoy, on the virtually lifeless ground at the site.

The resulting flood of nutrient-rich organic waste had an almost immediate impact on fertility in the country.

“Within about six months, the orange peel had become that thick black clay soil,” Treuer told Scientific American. Somehow a transition from the rough shells to a kind of muddy stuff enriched with fly larvae. ”

Despite this promising start, the conservation experiment did not last long after a rival juice maker named TicoFruit had sued Del Oro for alleging that its competitor [Del Oro] was “polluting a national park.”

The Costa Rican Supreme Court righted TicoFruit, and the ambitious experiment had to be ended, causing the site to be largely forgotten over the next 15 years.

Then, in 2013, Treuer decided to look at the site, while he was in Costa Rica anyway because of other research.

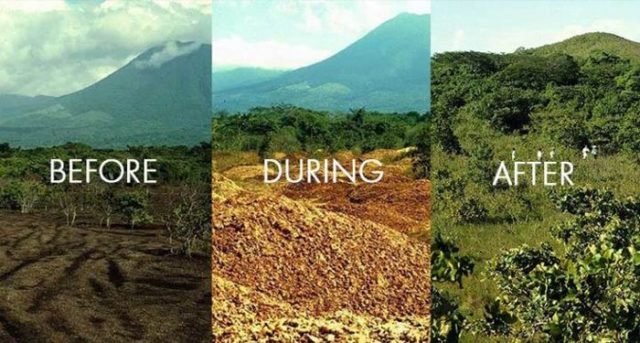

It turned out that the only problem was finding the former wasteland – a challenge that would require two trips to Costa Rica, as the desolate landscape had transformed beyond recognition into a dense, plant-filled jungle.

“The 1.80 meter sign with the area’s bright yellow lettering did not help much because it was so overgrown that we literally did not find it until years later,” Treuer told Marlene Cimons of Popular Science, “after dozens and dozens from site visits. ”

Comparing the site with a nearby control area that was not covered in orange peel, Treuer’s team found that their experimental compost pile produced richer soil, more tree biomass, and a greater variety of tree species – including a large fig tree that could accommodate three people with arms outstretched would need to span the trunk.

Nobody is sure about how the orange peel was able to effectively regenerate the site in only 16 years of isolation.

“That’s the big question we do not have an answer to yet,” Treuer told Popular Science.

“I strongly suspect that there was a synergy between crowding back grass and resuscitating heavily damaged soils.”

While the exact mechanisms remain a puzzle for the time being, the researchers hope that the remarkable success of this 16-year-old orange peel landfill will stimulate other, similar conservation projects.

Especially as richer forests, in addition to the double benefits of dealing with wastelands and revitalizing barren landscapes, also bind larger amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. This means that small areas like these could ultimately help save the planet.

“It’s a shame to live in a world of nutrient-poor, degraded ecosystems while having untapped nutrient-rich waste streams. We would like to see how these things are harmonized a bit, “said Treuer to Scientific American.

“This is not a farm license, just starting to dispose of its waste products in protected areas, but it means that [we] should think about how to conduct elaborate experiments to see if they are in their respective areas System can achieve similar results that benefit all sides.”